Every October in the weeks leading up to Halloween grimacing skeletons and gap-toothed pumpkin-heads seem to proliferate everywhere…

Every October in the weeks leading up to Halloween grimacing skeletons and gap-toothed pumpkin-heads seem to proliferate everywhere…In only a few years, Halloween in this country has gone from being a totally American and utterly un-British (and therefore inexplicable) holiday to being up there in the UK marketing and merchandising league with Christmas, Easter and Valentine’s Day.

There was a time when the only glimpse those of us on this side of the Atlantic ever got of the trick-or-treat world of Halloween was in Charles Schulz’ annual Peanuts strips in which Linus vainly waited in the pumpkin patch for the arrival of his own mythical invention, the Great Pumpkin!

Even though our stores are annually full of Halloween paraphernalia, there is precious little cultural knowledge in Britain about the Catholic feasts of All Hallows (or All Saints) and All Souls celebrated on the 1st and 2nd of November or of the European traditions, superstitions and amusements that preceded them on the 31st October known as All Hallows’ Eve or Hallowe'en…

Those who would like to understand more about the origins and multi-faceted accretions that comprise the dark festival of the turning year can, obviously, look them up in on-line or on-shelf encyclopaedias...

Those who would like to understand more about the origins and multi-faceted accretions that comprise the dark festival of the turning year can, obviously, look them up in on-line or on-shelf encyclopaedias...But, if you'll take my advice, you'll, instead, hitch a ride with the mysterious Mr Carapace Clavicle Moundshroud in The Halloween Tree, an autumnal conjuring trick by literary magician Ray Bradbury with haunting tombstone black-and-white illustrations by Joe Mugnaini.

The cadaverous Moundshroud leads a group of youngsters on a frantic time-travelling jaunt through the “deep dark long wild history of Halloween,” beginning within the shadow of the Halloween Tree…

The pumpkins on the Tree were not mere pumpkins. Each had a face sliced in it. Each face was different. Every eye was a stranger eye. Every nose was a weirder nose. Every mouth smiled hideously in some new way.

There must have been a thousand pumpkins on this tree, hung high and on every branch. A thousand smiles. A thousand grimaces. And twice-times-a thousand glares and winks and blinks and leerings of fresh-cut eyes…

By wing and kite and broomstick they fly on the winds of lost centuries from the darkness of the cave before the discovery of fire, and the rituals of Druid England with its scythe-wielding October God of the Dead, to the gargoyle-encrusted towers of Notre Dame; from the bone-and-mummy-dust tombs of Ancient Egypt through the Grecian Isles to the City of Rome and away to South America and the candles and sugar skeletons of El Dia de los Muertos, The Day of the Dead...

It is a journey that memorably explains how light and darkness, faith and fear have shaped a festival more wildly celebrated, perhaps, than understood…

So, maybe when the little terrors come around knocking our knockers next Halloween, we should slip a copy of Mr Bradbury's classic into their Trick or Treat bags - then they might know why they were doing what they were doing and, if nothing else, at least it wouldn't rot their teeth!

I find that re-reading The Halloween Tree - just as happens every time I re-read any of Ray's books - is an invitation to allow a bony finger to stir and prod among the leaf-mould and mummy-dust of my memories...

I find that re-reading The Halloween Tree - just as happens every time I re-read any of Ray's books - is an invitation to allow a bony finger to stir and prod among the leaf-mould and mummy-dust of my memories...I travel back in time twenty-six years,,,

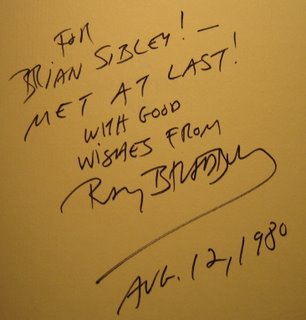

It is 1980 and, after six years of corresponding with Ray Bradbury, we met for the very first time when I interview him at the offices of his London publishers.

The book which I take with me on that occasion to ask him to inscribe is the first UK edition of The Halloween Tree...

Six years later, we meet for lunch in a restaurant on Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles and waiting for me under the napkin by my plate is an American edition of the book with an inscription and a golden Halloween Tree drawing by the author, studded with grinning pumpkin lantern stickers!

No wonder this book has always been special to me...

That lunchtime gift was given twenty years back and this year came another gift from Ray Bradbury: an e-mail in which he recounted a short history of how the Halloween Tree came to be planted and how it grew and put forth its unique autumnal fruits...

Here, with Ray's permission, is that story...

The Halloween Tree came about because I had lunch with [legendary Bugs Bunny animator] Chuck Jones forty years ago; he had just become a new friend.

The night before, an animated [Peanuts] film - The Great Pumpkin - had been on TV. My children disliked it so much that they ran over and kicked the TV set, along with me, because the whole idea of the Great Pumpkin supposedly arriving and then not arriving was incorrect to me. It was like shooting Santa Claus on the way down the chimney!

Chuck Jones and I agreed that we didn't like The Great Pumpkin, though we did admire Charlie Schultz, the cartoonist, very much. Then Chuck said, "Why don't we do a really good film on Halloween?" I said, "I think we could. Let me go home and bring something."

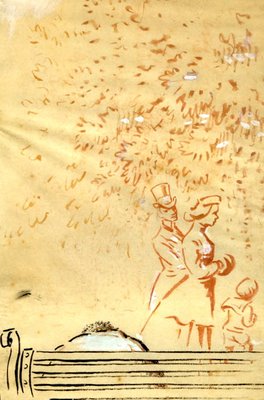

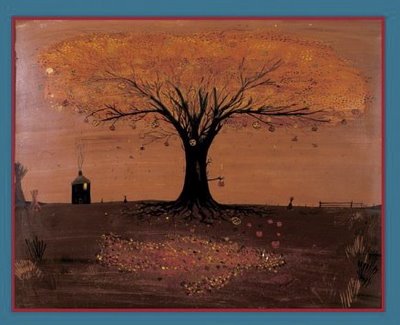

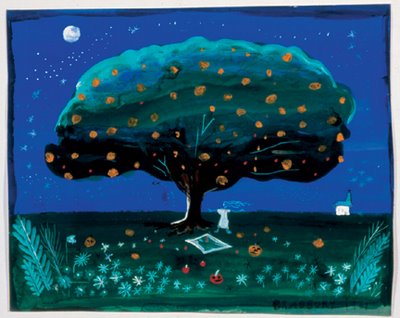

So I went home and brought Chuck a large painting of a Halloween Tree that I had painted down in the basement with my daughters a few years before.

Chuck took one look at it and said, "My God, that's the genealogy of the holiday. Will you write a screenplay on this?" I said, "Yes, hire me!" So Chuck Jones and MGM hired me to write a TV script called The Halloween Tree.

Several months down the road, MGM decided to turn its back on animation, so they closed their unit and fired Chuck and me. I had nothing to do then so I took the script and wrote the novel of The Halloween Tree.

Later I wrote a second script for the final animated film, which was done by Hannah-Barbera a few years later, for which I received an Emmy Award for the script.

About three years ago I produced Something Wicked This Way Comes at a theater in Santa Monica and on Halloween night my biographer, Sam Weller, drove me to the play and then home again at around 10:30 at night and on the way, in four different yards we saw that people had placed pumpkins, real ones or papier mache, lit with candles in trees in their front yards.

Now, there are Halloween Trees beginning to appear all over the United States and I realized that with my story and that picture that I painted down in the basement with my daughters more than forty years ago, I've changed the history of Halloween in the entire country.

I've discussed this with the Disney people and suggested that they invite me to Disneyland on Halloween night and put up a tree full of papier mache pumpkins and have me there to turn on the whole thing. They would make themselves and me part of the future history of Halloween because no trees existed forty years ago -- they began to appear only after my book and my film.

The Disney people haven't reacted so far because, I believe, the notice is very short. If we don't do it this year I'm hoping that Disney will invite me out next Halloween and initiate the birth of the Halloween Tree and the history of the holiday.

It's been an interesting experience for me and it thrills me to think that 100 years from now there will be Halloween trees all across our world...

For more information about Ray Bradbury and his books, read my profile of him on Gateway Monthly; and many pages of information on the excellent Bradbury Media.

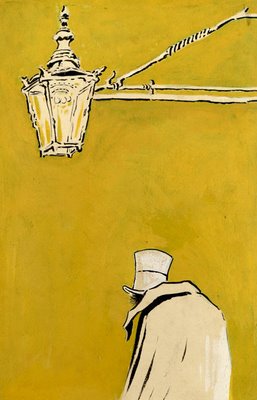

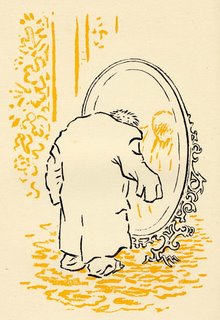

[Images: Peanuts © 1971 United Features Syndicate, Inc; illustrations to The Halloween Tree by Joe Mugnaini, © 1972 Alfred A Knopf, New York; the cartoon of Ray Bradbury is by myself and accompanied my first interview with him in 1980; the autumnal Tree was painted by Ray in c. 1960, the green Tree, some years later and both are featured in a superb limited edition of the book from Gauntlet Press.]

[Images: ]