Ray Bradbury’s

The Golden Apples of the Sun has worn many different covers over the years…

My original copy - sadly, long ago lost - was dressed in black with a roundel of purple grotesqueries that I later discovered were the work of Goya.

On the back was the word

IMAGINATION printed backwards!

It caught my eye one hot summer day when I was idly looking at an assortment of paperbacks on one of those swivelling bookracks outside my local newsagent’s shop.

A collection of twenty-two weird and wonderful tales, it had been named

The Golden Apples of the Sun by its author with a gracious nod to W B Yeats and sundry mythological sources.

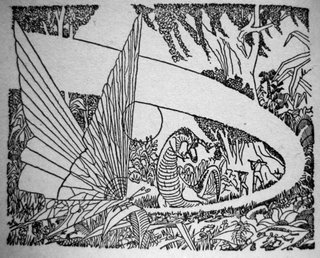

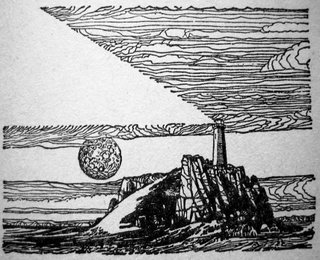

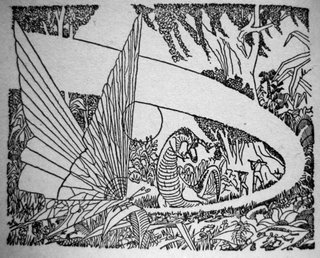

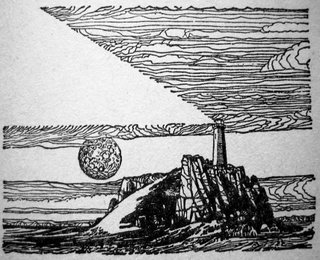

Some of these tales were about sea serpents and space ships; about witches and murderers and time-travelling big-game hunters who take a safari back into prehistoric times to hunt a living Tyrannosaurus Rex.

But by far the majority were about ordinary (and, therefore, extraordinary) people and the wildly ricocheting rollercoasters of their emotional lives: love lurching to hatred; despair soaring to joy; happiness plummeting to sorrow…

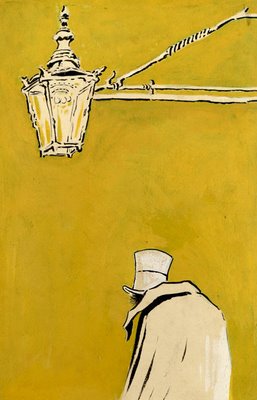

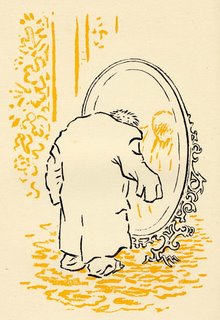

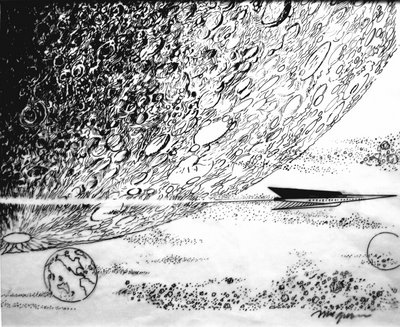

Each story had a headpiece by the artist, Joe Mugnaini, whose distinctive black and white decorations were a frequent embellishment to many of the author’s stories and book jackets.

I encountered Ray Bradbury at an age when wide-eyed childhood wonder was beginning to crumble in the face of budding teenage angst. It was a moment of apotheosis; a baptism; an epiphany…

I gobbled up

The Golden Apples in a day and wanted

more! I found them, soon enough, in library and bookshop, and was soon drinking down

Dandelion Wine, dosing myself with

A Medicine for Melancholy, burning with the paper-shrivelling heat of

Fahrenheit 451, leaping into the velvet darkness of outer space in pursuit of

The Silver Locusts and jumping astride the backwards-running carousel in

Something Wicked this Way Comes, about which I will write more on another occasion.

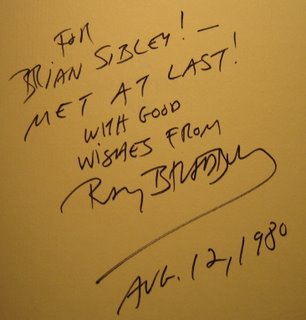

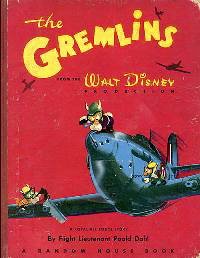

In 1974, many years after my first reading of

Golden Apples, I wrote the author a fan-letter. Ostensibly, it was asking questions about our shared passion for the work of Walt Disney, but that was merely an excuse to tell the Pied Piper that I was captivated by his music!

Did I expect a reply? With the arrogant confidence of a twenty-five year old, I probably did! And I was not disappointed…

Ray’s answer came in instalments: an envelope of cuttings and articles on Disney (scrawled across one in his ubiquitous capital letters: “LETTER FOLLOWS IN ABOUT 10 DAYS!”); the following month, a postcard with a contact address for a veteran staff member at the Disney Studio who might assist me with my research; then, another month on, the awaited

LETTER...

“This will have to be short," it began. "Sorry. But I am deep into my screenplay on

Something Wicked This Way Comes and have no secretary, never have had one… so must write all my own letters… 200 a week!!!”

Short it was

NOT! Ray signed off, added a post-script and then started another page and, picking up on a naïve comment from my original letter, let fly a barrage of counter-arguments, issuing challenges, demanding a re-think…

“P.S. Can’t resist commenting on your fears of the Disney robots… Any machine, any robot, is the sum total of the ways we use it. Why not knock down all the robot camera devices and the means for reproducing the stuff that goes into such devices, things called projectors in theatres? A motion-picture projector is a non-humanoid robot which repeats truths which we inject into it. Is it inhuman? Yes. Does it project human truths to humanize us more often than not? Yes…”

Closely typed - top to bottom, edge to edge - the letter exploded with thoughts and bristled with opinions.

I felt as if I had suddenly inherited a mentor, been adopted by a godfather, had received an embrace from a fellow lunatic-lover of strange and curious things and, totally unexpectedly and utterly undeservedly, had been given a present in the form of a Friend…

That is how it proved to be: a friendship that, to date, has spanned 32 years and is represented by stacks of letters, notes, cards and, most recently, e-mails; piles of books and mementos and memories of many meetings.

At one such, during the grand opening-day celebrations of Disney’s EPCOT Center (22nd October 1982), Ray autographed my copy of

Twice 22 (a volume combining

The Golden Apples of the Sun and

A Medicine for Melancholy) with an inscription unique to the day, the book and our shared passion for Disney.

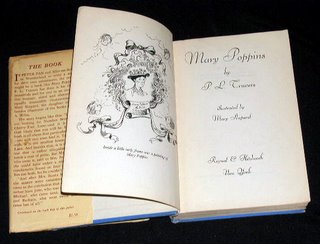

It was several more years before I managed to find a copy of the 1952 first edition of

Golden Apples to present to Ray for signing...

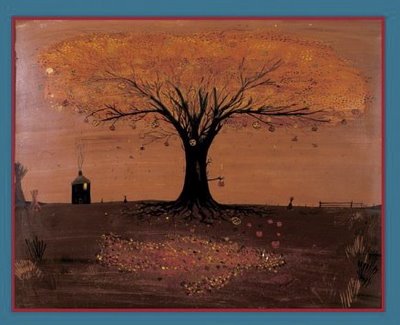

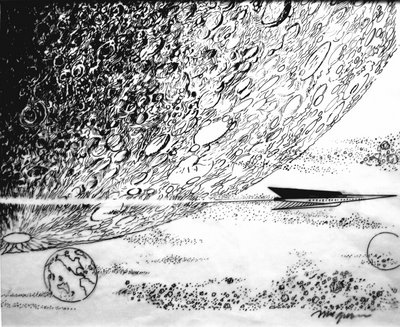

By that time, I had made a unique addition to my Bradbury collection.

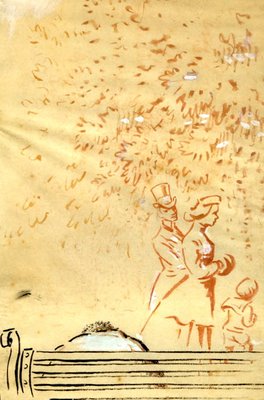

It appeared in a catalogue of animation art where it was described as: “Fantasy illustration showing a planet and a space ship. Signed by the artist”. The cataloguer obviously couldn't read the signature - and anyway 'Mugnaini' is not a common name - but I knew precisely

what it was and where it came from! It was the headpiece to ‘The Wilderness', the fourth story in

Golden Apples, and which (with the small amendment of an additional distant planet) had originally been used as the book's dust-wrapper design.

The picture now hangs in my study above a tottering pile of books authored by Ray Bradbury and our friendship continues to this day, with Ray still inspiring me, questioning me, clapping me on the back to encourage me and prodding me to think and to write…

In return, I have managed one or two small offerings, such as a few articles, a handful of radio dramatisations and the only gift I can ever truly give: unconditional love for a man who has made me see the world and myself, in a way I had never seen them before…

Read my interview with Ray,

The Brabury Machine here.

[Portrait of Bradbury: Yousuf Karsh]

With permission, I should like to share with you a few cyanide-scented sentiments and arsenic-flavoured accolades from another of my loo-side treasuries - The Little Book of Venom: A Collection of Historical Insults compiled by Jennifer Heggie

With permission, I should like to share with you a few cyanide-scented sentiments and arsenic-flavoured accolades from another of my loo-side treasuries - The Little Book of Venom: A Collection of Historical Insults compiled by Jennifer Heggie