As my BBC radio serialisation, The History of Titus Groan continues to be brought to life in Studio 60a of Broadcasting House, I have been reflecting on the pathways of happenstance that led me to Gormenghast.

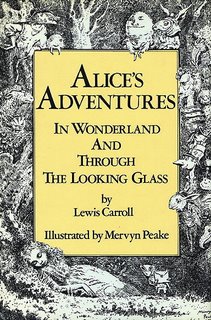

As my BBC radio serialisation, The History of Titus Groan continues to be brought to life in Studio 60a of Broadcasting House, I have been reflecting on the pathways of happenstance that led me to Gormenghast.It was Lewis Carroll who introduced me to Mervyn Peake: my fascination with the Alice books prompted me to start collecting illustrated editions and one of the earliest ones I stumbled across was illustrated by Peake.

Unlike almost every other artist who had ventured into Wonderland and Looking-glass World, Peake succeeded in throwing off the shackles of John Tenniel and produced pictorial visions for Alice’s adventures that matched the bizarre, often disturbing, text which they accompanied… Who else but Peake would have thought of giving the Carpenter a wood-grained face and, literally, finely chisled features?

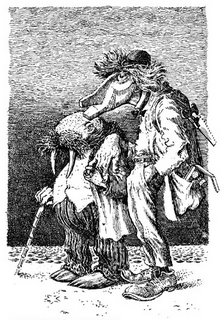

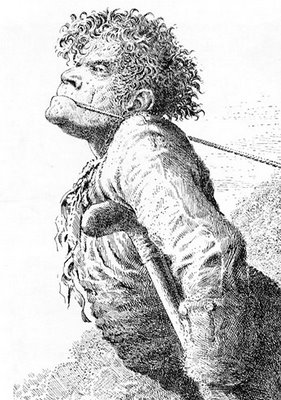

Peake’s Alice led me to his illustrated editions of Grimm’s Household Tales and those sea-faring sagas, The Hunting of the Snark, The Ancient Mariner and Treasure Island (below).

My delight in these drawings prompted me – with the impetuosity of youth – to write to the artist’s widow, Maeve Gilmore; and, to my great delight, I was immediately invited to tea at the then Peake home at 1 Drayton Gardens, Kensington.

After tea, Maeve took me into Peake’s workroom, pulled open a drawer and allowed me to browse through folder after folder of her husband's original illustrations.

It was while we were looking through the illustrations for Alice that I discovered that several the illustrations, as first published in Stockholm in 1946, differed from those in the 1956 British edition of the book with which I was familiar.

It was while we were looking through the illustrations for Alice that I discovered that several the illustrations, as first published in Stockholm in 1946, differed from those in the 1956 British edition of the book with which I was familiar.Being at the time, Secretary of the Lewis Carroll Society (and editor of its newsletter, Bandersnatch) this was a fascinating discovery that I was eager to write up. Maeve, sensing my enthusiasm suggested to Peake’s publishers that I be invited to edit what was the first definitive edition (right) of the Carroll-Peake Alice.

This assignment led to more afternoon teas and a deepening friendship with Maeve who – over the Earl Grey – coerced me into joining the Mervyn Peake Society (of which I would eventually become first Secretary and then Chairman) as well as encouraging me to discover Peake the writer as well as the artist.

I went away and read The Rhyme of the Flying Bomb, Shapes and Sounds and Mr Pye and, inevitably, turned my footsteps in the direction of that mournful mountain of masonry – Gormenghast.

Nothing I had ever read prepared me for that world of ruination and ritual; a realm of endless corridors burrowing through a sprawling edifice of broken, ivy-eaten stone; a cloistered universe inhabited by characters hopeless in their complacency, lost in their self-absorption or burning with the fire of ruthless ambition.

When I became Chairman of the Society of Authors’ Broadcasting Committee and had regularly to attend meetings at their offices at 94 Drayton Gardens, I saw Maeve more frequently: having lunch with her in the basement kitchen that she had entirely decorated (down to the Potterton boiler) with murals or enjoying generously measured gins-and-tonic in the back-parlour - or, as she called it, the 'petite salon'.

It was Maeve who encouraged me to offer the BBC a radio dramatisation of Titus Groan and Gormenghast and whilst she didn’t live to hear the Sony Award-winning production with Sting as Steerpike and a star-studded cast, she listened intently as I read her the scripts in the 'petite salon', and – after refreshing my G&T – offered insights and suggestions and generally guided me through the labyrinthine task.

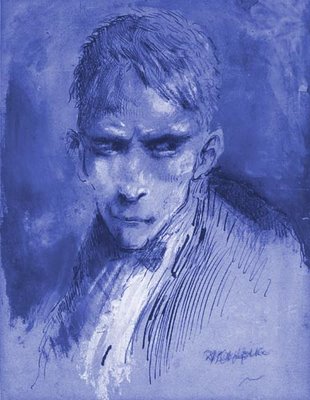

We often talked about how to get more of Mervyn Peake’s work back into print and looked many times through those folders of drawings and paintings filled with so many dazzling examples of her late husband’s stunning draughtsmanship – such as his then unpublished illustrations to Charles Dickens’ Bleak House with such brilliant pieces as the portrait of the icy and imperious Lady Deadlock, illuminated like a player in a Toulouse Lautrec theatre…

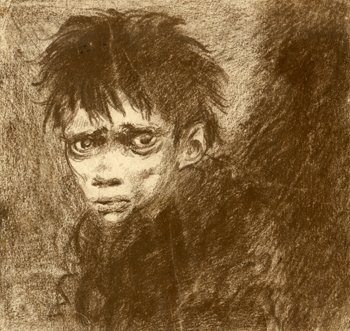

…and the haunting picture of poor, downtrodden Jo the crossing-sweeper with his fear-filled eyes and poverty-pinched features…

Maeve would have been thrilled that so many of those drawings and illustrations were eventually collected in the book, Mervyn Peake: The Man and His Art, compiled by her eldest son, Sebastian Peake, with Alison Eldred and G Peter Winnington.

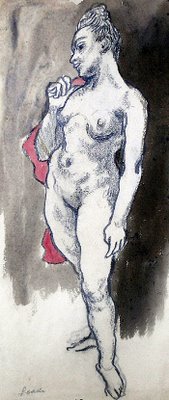

Maeve would have been thrilled that so many of those drawings and illustrations were eventually collected in the book, Mervyn Peake: The Man and His Art, compiled by her eldest son, Sebastian Peake, with Alison Eldred and G Peter Winnington.Published in 2006 by Peter Owen, this volume (more than any earlier collection) is stashed with examples of Peake’s multi-faceted talent: his daringly eclectic range of styles; his fearsome command of every media from the pencil-box and ink-bottle to the paint palette; and his seemingly inexhaustible capacity for perceptive characterisations that capture the comically absurd, the darkly macabre, and the sensually seductive…

I well remember attending the launch of this book at Chris Beetles Fine Art, London, where a selling exhibition of Peake’s work was also on show.

The price-list, naturally, was not reading matter for the faint-hearted or lily-livered, but, as with all such exhibitions, it costs nothing to look and to marvel at the skills of a unique craftsman whose reputation has now deservedly been rediscovered and is rightfully widely celebrated…

However - as is normal in the world of fine art – it is depressing to contemplate the vagaries of fame: remembering that Peake was an artist who, again and again throughout his life, was strapped for cash but who, if he were but alive today, might have expected a healthy cheque from Mr Beetles at the end of the show…

It also occurred to me at the time – looking around at the champagne-drinking chatterers attending the Private View – that, had he been there, Peake would have had his notebook out and been sketching madly…

Then I realised that he had already sketched a good few of the attendees and they were there for all to see --- framed and hung!

The room was papered with Peake’s people but it was also thronging with them too, milling around, unwittingly scrutinising their twins and wondering at their beauty, shuddering at their monstrousness, laughing at their ludicrousness…

The likenesses in line had their counterpoints everywhere: that man with the lantern jaw; this one with the parrot-beak nose; the tall woman with no chin and gimlet eyes; the dwarf with the beetling brows and tombstone teeth, the walking cadaver with the hooded eyes...

Was I fantasising?

Perhaps, I thought, but then, suddenly I noticed – just beyond Jeffrey Archer – the portrait of Mr Chadband from Bleak House being intently scrutinised by none other than Mr Chadband himself!

For more information about Mervyn Peake: the man, his art and his writings visit the official Mervyn Peake website.

[All images: © The Mervyn Peake Estate]